Notes on the Yokohama Triennale 2014

By Christine Eyene

First published: 6/10/2014

It was there somewhere, on the bottom rows, in one of the corners where dust tends to build up, on top of books laying unread. This one had only been read once. It was a compulsory read, part of high school curriculum, and has followed me since. As I set off for the airport on my way to the Yokohama Triennale, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953) was the last but most important item added to my luggage. After more than twenty-five years, I revisited my aged copy of the classic that inspired the theme of the triennale entitled “Art Fahrenheit 451: Sailing into the Sea of Oblivion”, curated by Japanese artist Yasumasa Morimura.

In Tokyo, I grabbed a local cultural magazine that featured an insert on the triennale. In it was described some of the emotions visitors could expect from the event: between loss and confusion, inspiration and fulfillment. I, for one, was intrigued by the choice of an American literary source as the triennale’s conceptual framework. With this questioning came the immediate realisation that I had come to Japan with the anticipation of being submerged in a sea of Japanese and East Asian contemporary art. Instead I found the sort of exhibition to which one is usually exposed in the West, both in form and content.

One could argue that the Yokohama Triennale is an international art event. In this respect, it makes sense to present to the Japanese audience internationally acclaimed mainstream artists and historical figures. That being said, out of the 44 or so listed individual artists and collaborative practitioners exhibited at the Yokohama Museum of Art, to take this venue as an example, about 26 are Westerners as opposed to 18 Japanese and East Asian artists.

This observation is no petty quibbling over statistics. Rather it shows the extent of Western hegemony on artistic discourse. Furthermore, this replication of Western models is paired with a symptomatic exclusion of large chunks of artistic practices from the South. It’s hard to believe that Yokohama Creative City Center hosted a major symposium on contemporary African art just last year. This leads one to wonder what Morimura understands by “the world” when he asks in the introductory chapter of his exhibition “What is in the Center of the World?” A question which answer is to be found in Michael Landy’s Art Bin (2010).

But let’s step back a bit, to the beginning of the exhibition. Upon approaching the museum, the visitor is welcomed by Wim Delvoye’s Flatbed Trailer (2007), a 15-m long laser cut steel lorry sculpted in Gothic architectural style. The piece may illustrate the notion of “unmomumental monuments” with its deceptive aesthetics, but its scale – just like Landy’s “monument to creative failure” – does make it a grand statement.

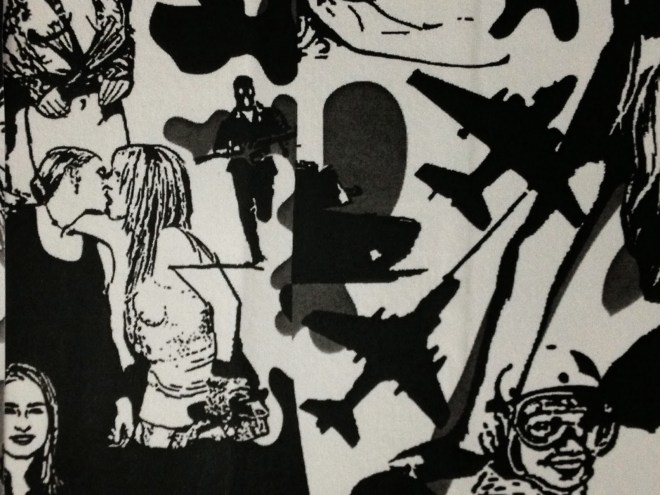

At this point, there are two options for Western-based visitors. Either to experience the exhibition with a feeling of déjà-vu, or allow oneself to read familiar works anew. Opening oneself to the latter is the best way to be drawn into the world imagined by Morimura, starting from the first chapter: “Listening to Silence and Whispers”. Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist Drawings (Fragments) (ca. 1915-1915); John Cage’s 4’33’’ (1952) original scores by David Tudor and facsimile version; John Smith’s plain whites, Tomoharu Marakami’s deep black, Karmelo Bermejo’s Blank (2013) canvas made of white oil paint, and his Certificate of Authenticity, invisible ink on transparent sheet, all partake of a process of purifying one’s gaze, clearing one’s mind, ridding oneself of all knowledge and entering the space afresh. Almost like reaching, in the words of Roland Barthes, a “degree zero”, a “neutral zone” of reading. Morimura offers the visitors a space for silent music and silent painting. A return to basics in painting, with a colour spectrum that begins and ends with monochromatic whites and blacks, and the rationalism of pure geometrical forms. Painting as matter and material, as form and medium.

The exhibition continues with Belgian artist René Magritte’s series The Fidelity of Images (1935) and Marcel Broodthaers Interview with a Cat (1970). These are followed by works from artists Yongik Kim (Korea) and Hiroshi Kimura (Japan) which reading was less easily accessible since they are mediated through writing and translation. But wasn’t this the object of this trip? To be immersed in local culture? One after the other, the chapters reveal the narrative conceived by Morimura, each work engaging the viewer to various degrees, according to one’s receptiveness and sensitivity.

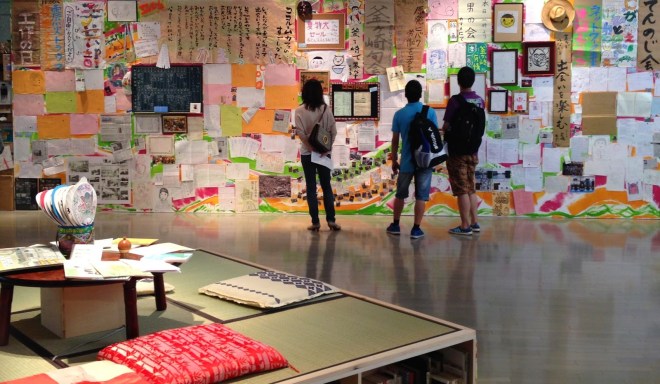

Chapter 2: “Encountering a Drifting Class Room” presents Kama Gei, a community project run by the non-profit organisation The Room for Full of Voice, Words, and Hearts (cocoroom), founded on the idea of learning from each other. The project addresses the social effects of recession in Kamagasaki, Osaka, and the correlated issues of ageing population, unemployment, medical care and housing. A multidisciplinary environment, Kama Gei brings together various graphic elements, video documentation, and a social space activated during the triennale through a series of performances and workshops.

Chapter 3: “Art Fahrenheit 451” is a direct quotation of Bradbury’s science fiction novel. In that sense it could almost be considered as the central focus of the show. It opens with Taryn Simon’s A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I-XVIII (2008-11), and includes a number of works by Edward and Nancy Keinholz casting a critical gaze on the society of their time and its future, in other words, our present society. Dora Garcia’s installation Fahrenheit 451 (1957) (2002) consists of stacks of books with inverted typo, that are impossible to read, other than with the help of a mirror. Her piece plays on the difficulty to access meaning while being equipped with the knowledge of the sign system that is the Latin alphabet.

Another important piece is Moe Nai Ko To Ba (The Only Book in the World), created for the triennale. Displayed on a raised reading desk, the Book compels the reader to the performative act of walking up a few steps to access it, with care, using gloves, under supervision of a keeper/invigilator, in full view of the exhibition room. The eight texts and art works by Anna Akhmatova, Elfriede Jelinek, Vera Miliutina, Shiga Lieko, Nakayaka Kikochi, Kim Yongik, Matsui Chie and Morimura himself, all dealing with oblivion, form “an exhibition within an exhibition”. This “Book of Oblivion” will be destroyed at the end of the triennale in homage to Bradbury’s novel.

The reflection on oblivion could however extend much further. Indeed as mentioned earlier, it is oblivion that has led to the complete erasure of art practices from large parts of the South, and consequently has prevented to open the curatorial scope to places which stories are similar to situations evoked in Bradbury’s novel. While the resonance between the recent conflict in Gaza (with its global media manipulations ) and Bradbury’s apocalyptic vision were certainly unplanned, other correlations are, on the other hand, attested by history. The African continent is a significant case where material productions, receptacles of history, tradition, knowledge, culture, religion, have been destroyed and pillaged in the same violence as the autodafés described in Bradbury’s book.

Likewise, when at the end of the novel the main character, Montag, joins a group of fugitives who are in fact scholars who have memorised books and become books themselves, one cannot but associate it to intangible cultural heritage, oral history, and the role of the griot.

Although Africa is the only case mentioned here, the same observation could probably be made with regard to other regions of the world. In other words, one might say that this was a missed opportunity to genuinely tackle notions of oblivion, erasure and silencing of a number of influential contemporary arts and cultures. That was, in my view, one of the missing elements that a 21st century international triennale of contemporary art should not have failed to address; if not in the exhibition, as part of the public programme, or in the written output.

The triennale spreads out over 11 chapters that will not all be discussed here. Two of them, chapter 10: “Days after the Deluge” and 11: “Drifting in a Sea of Oblivion”, are located at Shinko Pier. This part of the triennale was more what I came for. As subjective experiencing an exhibition can be, these two chapters felt like they lent themselves more easily to open discourse, interpretation and questioning, as opposed to being authoritative statements canonised by a physical display in the imposing walls of a national museum.

This section contained a majority of Asian artists and offered a better insight into the region’s art scene, notably with the inclusion of a selection from the Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale. My personal highlights were, to name but a few, Japanese artists Hiromi Tsuchida and Tadashi Tonoshiki who both addressed the multifold impact of Hiroshima; Emiko Kasahara’s series on the complex relationship between religious offering and the expectation of a reward; and Shinro Ohtake’s shed containing various sorts of relics, memorabilia or found objects, creating a visual environment of its own. So were Melvin Moti’s projection and book on the empty Hermitage Museum, No Show (2004); Akram Zaatari’s Her+Him (2001) around some semi-nude photographs taken by Van Leo; Bas Jan Ader and Jack Goldstein’s self-sacrificial, absurd or pointless video-performances, and of course, Ana Mendieta.

Two other excellent projects need to be mentioned: “Dreams of East Asia” at BankART Studio with notably amazing works by Daisuke Kuroda, Yukinori Yanagi, Sumi Kanazawa, Toshiyuki Kuwabara, Anneke Pettican & Spencer Roberts, and a spectacular installation by Tadashi Kawamata.

In Koganecho, Canadian-based Japanese curator Makiko Hara organized “Fictive Communities Asia“, as part of Koganecho Bazaar 2014, a festival investing the arcades of a rail bridge in an area undergoing rehabilitation. Alongside the festival was also held “Alternative Route: Symposium on Contemporary Art, History and Current Issues in Asia” at Yokohama Creative City Center. Lack of time did not allow me to visit all of Koganecho’s exhibition spaces. But what was missed in exhibition visits was gained in human encounters.

Being in Yokohama and Tokyo was a case of literally jumping into the unknown. While my first visit in 2013 took place in the comfort of an international symposium on contemporary African art, my second visit was marked by the total absence of peers. A chance encounter on the underground with Taque Hirakawa and a friend of his, young Japanese fashion designer Dorothy Vacance – wearing a stylish dress she designed with “African” fabric – led to more encounters. First was Johnnie Walker, founder of A.R.T. Artist Residency Tokyo, then Tokyo-based Scottish artist’s Jack McLean. A couple of days later, at Maison Hermès in Ginza, Tokyo, at a surreal afternoon of wedding ceremonies by Paris-based Japanese artist Tsuneko Taniuchi, Jack introduced me to Shai Ohayon founder of The Container, a gallery in a shipping container installed in a hair salon in Tokyo’s Nakameguro area. Shai is showing promising groundbreaking emerging local and international artists. The Container has received rave reviews from the very first exhibition, proving the potential of such experimental curatorial approaches and forms of display.

Not far from The Container, Naoko Hiriuchi curator at Arts Initiative Tokyo, made some time to meet me and introduce me to her institution. AIT has hosted several African visual artists and curators in residency. She has also informed me of Arakawa Africa, in Arakawa ward, Tokyo, a project focusing on cultural exchanges with African artists from various disciplines.

I left Yokohama in August as Typhoon Halong was approaching. Today Japan continues to be hit by extreme weather threats with Typhoon Phanfone making substantial damage and claiming lives. The Yokohama Triennale, BankArt Studio and Koganecho Bazaar exhibitions continue to 3rd November 2014. Times and events may vary depending on the weather. The Yokohama Triennale information desk is recommending extra caution while traveling during the typhoon.

Follow

Subscribe

Sign up with your email address to receive our latest news.

© eye.on.art 2024 – All rights reserved.